O

Trailer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Xa1aiVkiT4

Purchase links:

https://books2read.com/GreatPlain

Chapters on SoundCloud

https://soundcloud.com/j-arlene-culiner/those-absent-on-the-great-hungarian-plain-the-hungarian-count

What people are saying about Those Absent:

Part history book, part travelogue, Jill Culiner’s “Those Absent on the Great Hungarian Plain” is a fascinating literary journey, exposing anecdotes of rural life and anti-Semitism in the late nineteenth century to modern days, in search of forgotten Hungarian Jews. An intriguing and frank investigation of the region’s daily life, its common beliefs and rarely mentioned truths. Highly recommended.

Mel Cederbaum, Executive Director, Toronto Workmen's Circle

Jill Culiner has written an incredibly evocative book about the lost Jews of Hungary, about a time and place that history has forgotten or perhaps doesn’t want to remember. Living for some years in small towns in rural Hungary, she discovers that no one seems to be able to recollect how the Jews disappeared or were murdered and how the pogroms continued well after the war. The book is part history, part detective story, part personal memoir. It brings to life a cast of characters fitting for a Dickensian novel. It deals with the fallibility of memory, with the nature of prejudice and persecution, and with the past as both history and fiction. It deserves to be read not only as a work of a neglected slice of history but equally as a treatise on human nature.

Michael Talalay, Senior Lecturer, Regents University London

Jill Culiner vividly recounts her relentless six year search for the truth about the fate of the Jews who returned from the Nazi death camps to Kunmadaras; reporting the confessions, memories and testimonies of the local residents who she cajoled, charmed, and challenged into acknowledging the Pogrom of 1946, and puts it all into a complex but lucid and rich historical context. Part memoir, part travelogue, part history, part elegy, this multi-layered homage to the Great Hungarian Plain embraces its majesty and tragedy at virtually the last possible moment.

Robin Roger, psychotherapist, writer, reviewer

The long history of hatred toward the Jews combined with the exploitation and misery of the peasants have forged Hungarian identity. The Jews are absent, but the roots of anti-Semitism are still present. Despite modernisation, progress, and Hungary's transition from communism to the European Union, Jill Culiner’s Central Europe is plagued by the same demons that led to the tragedies of the past century.

Dr Marcel Calvez, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, University of Rennes, France

In a kaleidoscope narrative of village life, coarse xenophobia and cruelty contrast with acceptance, friendship and laughter. The horror of the past is concealed, yet Culiner finds compassion in human failure.

Penny-Lynn Cookson, Art Historian, Writer

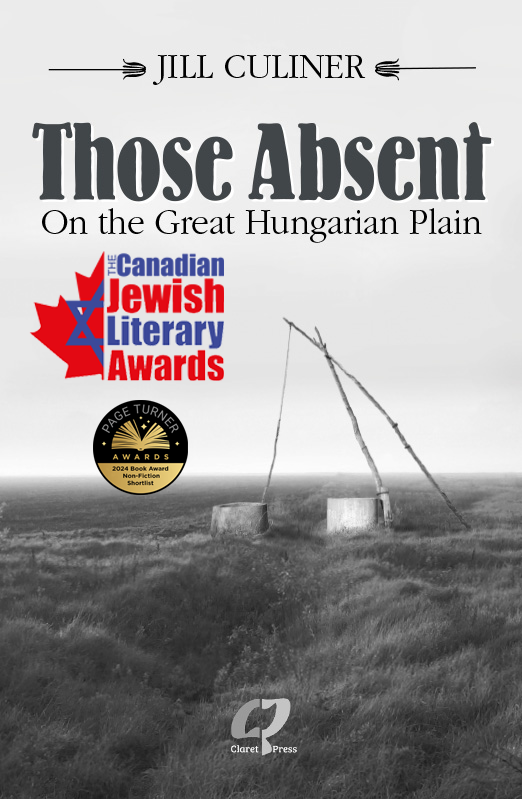

Non-fiction/Biography/Travel/History/Memoir

Those Absent

on the Great Hungarian Plain

Page Turner Book Award Finalist

In 1999, I was preparing a UNESCO-sponsored photographic exhibition for the Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation in France: the theme was Europe’s vanished rural Jews. Although the Jewish world had been largely exterminated during WWII, I would travel through Central Europe and the Baltic States, search for its trace in architecture and local memory.

One stop in my journey was Hungary, home to Europe’s second-largest Jewish population in 1914. Although now a popular tourist destination as well as a magnet for heritage travel, Hungary is one of Europe’s least-known countries. Its long history, complicated by intermittent foreign dominance, has been obscured by fantastic myth; and its Finno-Ugric language is impenetrable to most. To further blur understanding, modern tourism satisfies itself with incessant movement, colourful showmanship and selfies taken in emblematic settings. Yet to discover, even imperfectly, an area, a country, a mentality, it is necessary to go slowly (even on foot), to tarry in places never mentioned in guidebooks or on travel sites.

I intended to spend ten days in the country, taking photos in unspectacular rural communities. But in a small town on the Great Plain, I was welcomed by a friendly local group — the affable but bibulous Karcsi, bar-owning Ildikó, Kata, the eternal party girl, Tarzan, black-marketeer and corrupt night watchman, Janci, a musician who refused Hungarian music in favour of elevator ‘noise’ and Udo, the naïve Austrian. And I returned so often to hear their stories that my visits evolved into a residency of six years.

Local society was an uneasy mix. Retired communist officials lived elbow-to-elbow with their victims – nobles who had lost their lands, expropriated peasants and those who had endured torture. Alongside Hungarian-Swabian survivors of post-war ethnic cleansing, there were German retirees as well as previous members of the Hitler Youth Movement; and there were returning Hungarians who, slipping out of the country in 1956, had become lucky elsewhere. For all, admission to the EU in 2004 brought change that was rapid and relentless.

The agricultural sector was unprepared for the influx of cheap foreign produce and the devaluation of local commodities. Struggling with the rising cost of food, housing and utilities, few could conceive of acquiring the flashy cars, large screen televisions, computers and big new houses advertised everywhere. Huge supermarkets were appearing, yet unable to shop in them, villagers could simply go up and down the aisles, marvel at what was being offered and dream that one day they, too, could participate in the consumer society. Because all that was familiar – traditional music, centuries-old customs and local architecture – was disappearing, reassurance came in the political promises of an authoritarian populist leader and a violent hatred of those eternal scapegoats: the Roma, and the (largely vanished) rural Jewish community.

Prologue

I keep hearing that journalists should be truth crusaders, but that’s not right. All you need is curiosity and the ability to convey what you see without colouring it in any way.

B. James, former foreign correspondent, UPI

The Count, a slight man with a fine moustache, possessed exquisite manners and great dignity – qualities scarce in our howling arriviste milieu. I was a scrawny and sulky child of twelve, but he was the first man to kiss my hand, thereby earning my eternal loyalty.

Along with 200,000 other Hungarians, the Count had clandestinely slipped out of his country during the 1956 Uprising. More fortunate than most, he had managed to smuggle out rolled-up paintings, those once gracing the walls of his family’s pillaged and ruined manor. His was a tragic story, but it could have been far worse: under the post-war communist regime, Hungarian aristocrats had been persecuted, sent to horrific prison camps, or sentenced to death. Alive and well, but with no financial resources here in his new country, Canada, the Count was obliged to sell the precious artworks.

Thanks to an enthusiastic collector – my father’s square-shaped multi-millionaire crony – the Count appeared in our life along with other colourful characters: the millionaire’s buxom mistress with her rigid yellow coiffure, and a ruddy clutch of businessmen eager to insert culture into their splashy mansions. My father, although an enthusiast, lacked the funds to purchase the finest beauties – a Vlaminck or two, several Courbets and a Modigliani.

Because the Count, inhabiting a flophouse in downtown Toronto, had no place in which to store invaluable works, several came to nestle, albeit temporarily, in our house: what thief would imagine such pearls stored in a suburban lookalike? My mother, soured by my father’s financial insufficiency, set out to copy the Modigliani hanging on the mauve wall above our yellow upright piano – she was an adequate amateur painter. Thus, when the original departed weeks later, her admiring lady friends believed it was still in our possession.

Back then, I couldn’t have cared less about fine art, but was thrilled to bits when the Count gave me a necklace (not to be worn until I was older). It was a beautiful piece, a complicated wreathing of gold leaves studded with tiny pearls, a flowery centre with a small diamond, and one uneven pearl droplet: easy to imagine it had been worn by a Magyar princess in some forbidding castle. He also presented me with a record of traditional Hungarian music: how entrancing the sweeping melodies, how exquisite the cimbalom. Thus, he opened the world for me, and Hungary became a romantic place I longed to see.

The multi-millionaire and his cronies soon purchased the Count’s collection; my father acquired a few lesser paintings at a cheaper price. All was well. Until, abruptly, proud acquisition became rage and dismay. It was discovered that the paintings were forgeries and the Count had disappeared. Further investigation revealed he was no Hungarian. Instead, he came from neighbouring Quebec, worked hand-in-hand with a highly talented French-Canadian forger. Both were sought by the police. My mother’s fake Modigliani journeyed from the mauve wall to the trash can; visits from the multi-millionaire and mistress ceased (four decades later, my father claimed he had also shared the brash lady’s favours); and my father’s business buddies no longer talked fine art.

Still, despite my itinerant life and endless mishaps, that beautiful necklace has remained with me, as have my curiosity about Hungary and my love for its traditional music.

***

The name Hungary is a misnomer, harkening back to the country’s brief occupation by the Huns in the fifth century. Killing their elderly, crucifying prisoners, reading the future in heated bones and entrails, scarifying their faces, flattening their children’s noses and deforming their skulls into an egg shape, dressing in a mess of mouse and rat skins, wearing horns, dying part of their hair red but shaving the rest, reeking horrifically – olfactory aggression set them apart from more fastidious mortals – the Huns easily inherited the sobriquet ‘barbarian’. Under the notorious Attila, known for his wild rages, they pillaged, murdered and enslaved their way across Europe. As they did, the conquered peoples emulated their fashions.

When military success flagged, the Huns retreated to the banks of the Tisza River where, after barbaric overindulgence during his wedding with the beautiful Ildikó, Attila was suffocated by a nosebleed. The Hun’s glorious moment was over: squabbling amongst themselves, routed by resentful locals, they withdrew back east, leaving behind their name and an enticing myth of buried treasure that dreamers have searched for over centuries.

In Hungarian, however, the country’s official name is Magyarország (or Magyar country). Originating in the Ural Mountains, the Magyars or Megyeri, were a Nordic herding and fishing people. In around 2000 BCE, one group began migrating southward. In the ninth century, settled in the area around Etelköz in Khazaria, they were being decimated by incoming fearsome Turkic Pechenegs:

In one dense mass, encouraged by sheer desperation, they shout their thunderous war cries and hurl themselves pell-mell upon their adversaries, pushing them back, pressing against them in solid blocks, like towers, then pursuing them and slaying them without mercy.

Banding together with Jewish and Muslim Khazars and Khabars, Huns, Sicules, Kalizes, Alans, Slavs, Onongurs, Avars and Bulgars, the Magyars fled to the Carpathian (Pannonian) Basin, where, under their leader Árpád, they quashed local Slav residents, joined ranks with Vikings and set out to defeat Bavarians, ravage northern Italy, the Balkans, Constantinople, Lorraine and Burgundy. So dreaded were the Magyars, that the word ‘ogre’ was (falsely) said to be a corruption of their name. Finally, weakened by two major military defeats, they returned to the Carpathian Basin, settled down and founded their country.

On the Great Hungarian Plain

The Great Hungarian Plain Now and Then

Nous avons besoin de votre consentement pour charger les traductions

Nous utilisons un service tiers pour traduire le contenu du site web qui peut collecter des données sur votre activité. Veuillez consulter les détails dans la politique de confidentialité et accepter le service pour voir les traductions.